In this article, we’ve collected some fun and interesting images from New Year’s Eve celebrations from times long gone.

In many countries, New Year’s Eve is celebrated by dancing, eating, drinking, and watching or lighting fireworks. The celebrations generally go on past midnight into New Year’s Day, 1 January.

In the United States, New Year’s Eve is celebrated via a variety of social gatherings, and large-scale public events such as concerts, fireworks shows, and “drops”—an event inspired by time balls where an item is lowered or raised over the course of the final minute of the year.

The earliest known record of a New Year festival dates from about 2000 BCE in Mesopotamia, where in Babylonia the new year (Akitu) began with the new moon after the spring equinox (mid-March) and in Assyria with the new moon nearest the autumn equinox (mid-September).

For the Egyptians, Phoenicians, and Persians the year began with the autumn equinox (September 21), and for the early Greeks, it began with the winter solstice (December 21).

On the Roman republican calendar, the year began on March 1, but after 153 BCE the official date was January 1, which was continued in the Julian calendar of 46 BCE.

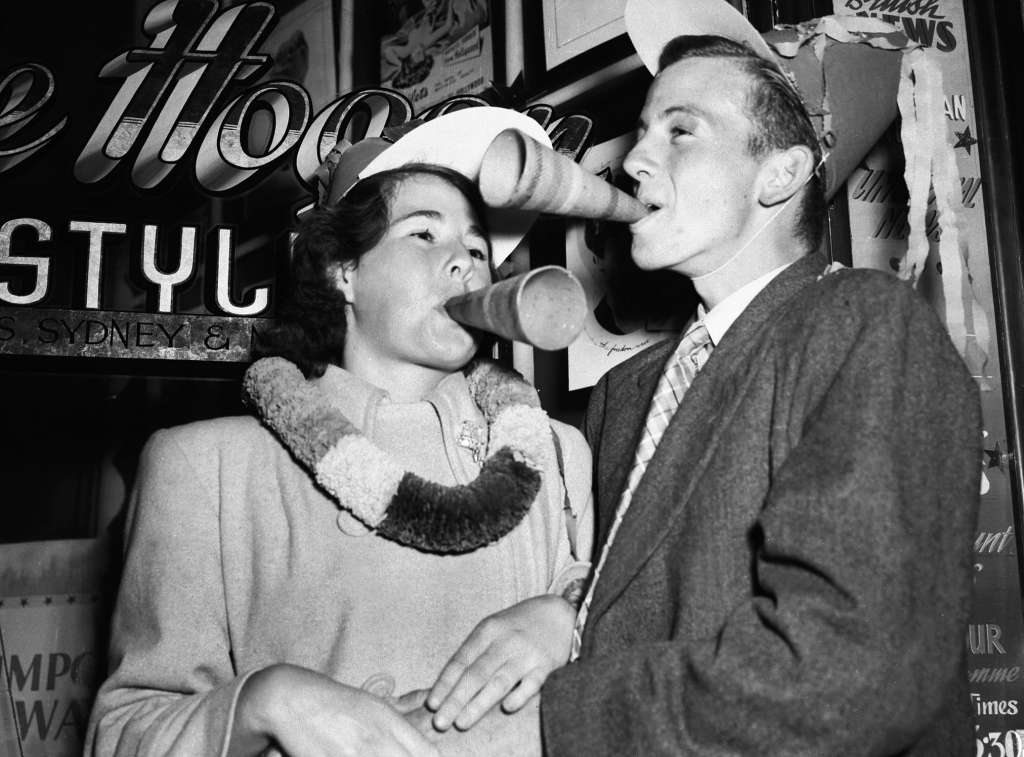

A couple ring in the New Year with party blowers and streamers, circa 1930.

In early medieval times, most of Christian Europe regarded March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation, as the beginning of the new year, although New Year’s Day was observed on December 25 in Anglo-Saxon England. William the Conqueror decreed that the year begins on January 1, but England later joined the rest of Christendom and adopted March 25.

The Gregorian calendar, adopted in 1582 by the Roman Catholic Church, restored January 1 as New Year’s Day, and most European countries gradually followed suit: Scotland, in 1660; Germany and Denmark, about 1700; England, in 1752; and Russia, in 1918.

A barman on duty at the cocktail bar of Hector’s Devonshire Restaurant in London on New Year’s Eve is seen preparing a cocktail. Shaken not stirred, 1930.

Many of the customs of New Year festivals note the passing of time with both regret and anticipation. The baby as a symbol of the new year dates to the ancient Greeks, with an old man representing the year that has passed.

The Romans derived the name for the month of January from their god Janus, who had two faces, one looking backward and the other forward.

The practice of making resolutions to rid oneself of bad habits and to adopt better ones also dates to ancient times. Some believe the Babylonians began the custom more than 4,000 years ago. These early resolutions were likely made in an attempt to curry favor with the gods.

Revelers at the Piccadilly Restaurant, London, celebrating the New Year, 1931.

Symbolic foods are often part of the festivities. Many Europeans, for example, eat cabbage or other greens to ensure prosperity in the coming year, while people in the American South favor black-eyed peas for good luck.

Throughout Asia, special foods such as dumplings, noodles, and rice cakes are eaten, and elaborate dishes feature ingredients whose names or appearances symbolize long life, happiness, wealth, and good fortune.

Because of the belief that what a person does on the first day of the year foretells what he will do for the remainder of the year, gatherings of friends and relatives have long been significant.

The first guest to cross the threshold, or “first foot,” is significant and may bring good luck if of the right physical type, which varies with location.

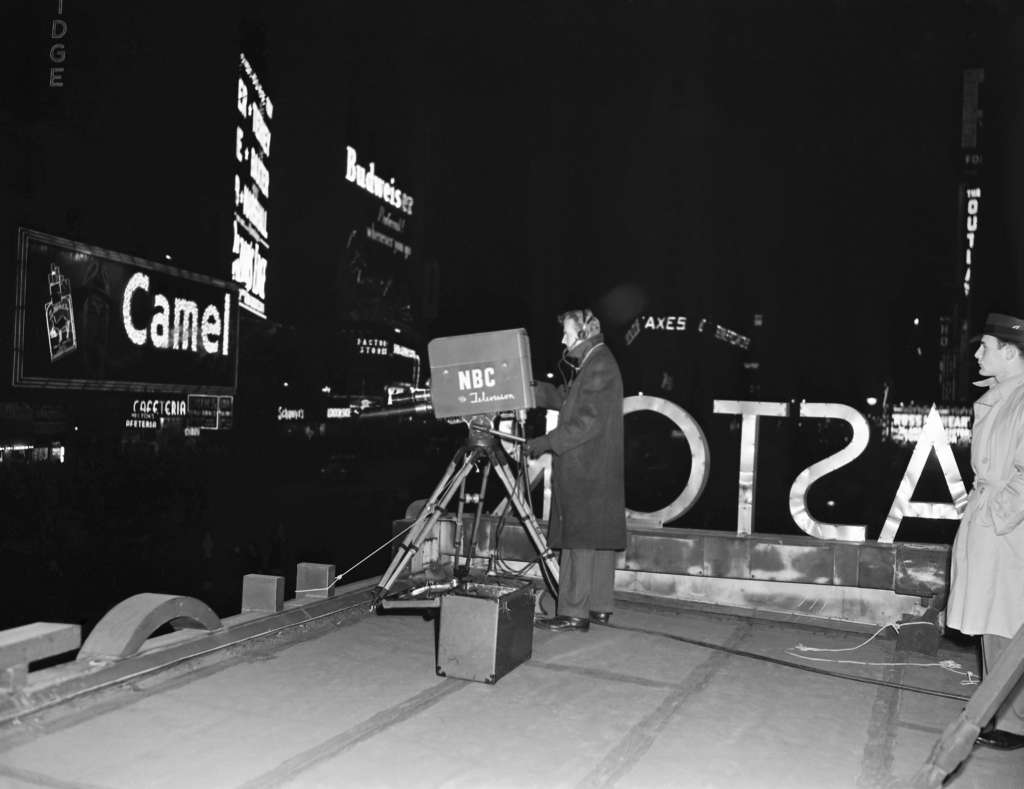

Public gatherings, as in Times Square in New York City or in Trafalgar Square in London, draw large crowds, and the countdown to the dropping of an electronic ball in Times Square to signify the exact moment at which the new year begins is televised worldwide.

New Year’s Eve revelers at the Piccadilly Hotel in London. December 31, 1931.

American actress Clara Bow holds up a large card while actor Larry Gray inscribes a New Year’s greeting with a giant pen, 1935.

Members of the Kensington Studios having a tea break as they prepare their costumes for the Chelsea Arts Ball, 1935.

A group of people in formal attire celebrate New Year’s Eve at the El Morocco nightclub in New York City, circa 1935.

Seasonal greetings from the original Hollywood sex symbol, Mae West, 1936.

A group of friends sitting on a car roof in London while celebrating the arrival of 1936.

New Year’s Eve Party In France, 1937.

A baby in his buggy is holding a new year’s eve poster with a good advice for the new year, 1937.

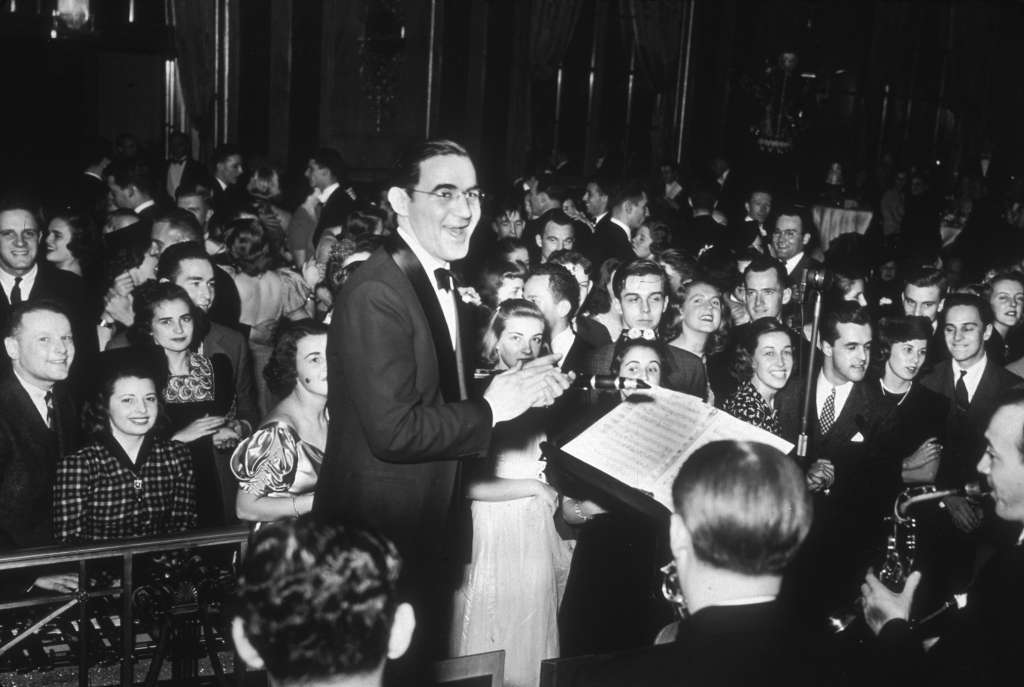

American jazz musician and bandleader Benny Goodman and his orchestra play for an enthusiastic audience during a New Year’s Eve dance at the Waldorf Astoria, New York City, 1938.

Entertainment by dancer Margarita Buencore at Webster Hall New Year’s Party, 1938.

Revelers recovering from New Year’s Eve celebrations on the steps of Grand Central Station, New York, circa 1940.

Employees of the Diamond Horseshoe cleaning up after a New Year’s Eve party in 1940 in New York.

New Year’s Eve in France, 1940.

Partiers in New York City on New Year’s Eve, as 1941 turns to 1942.

Soldiers and civilians celebrating the New Year in a nightclub, 1942.

A three-year-old boy accompanies his parents to a New York nightclub to celebrate New Year’s Eve. At five in the morning, he is still welcoming in the New Year with a bottle of milk, 1943.

British actress Ida Lupino smiling at a friendly sailor as she cuts a cake which reads Happy Victory Year, 1944.

Olga San Juan posing for a publicity still with nautical theme bearing message, 1944.

A studio portrait of two New Year’s Eve revelers, 1945.

Part of the New Year’s entertainment from Times Square, 1946.

A cameraman records the New Year’s Celebration in Times Square, 1946.

New Year’s Eve revels in London, 1948.

Actor Marie Wilson, wearing evening clothes and a party hat, and surrounded by streamers and balloons, celebrates New Year’s eve, 1948.

Dancers on New Year’s Eve celebrations at the Trocadero Restaurant, Leicester Square, London, 1949.

Nina Foch and dress designer Jean Louis sipping champagne at Samuel Spiegle’s New Year’s Eve party, 1949.

New Year’s Eve celebration, 1957.

Italian actor Ugo Tognazzi, his fiancee Caprice Chantal, British actor Anthony Steel and his wife, Swedish actress Anita Ekberg, during a diner in Saint Vincent Casino, Piedmont, on December 31, 1958.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress / Britannica / Py / Flickr).