A tree protrudes from a house tossed by the flood.

The South Fork Dam was built between 1838 and 1853 by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to provide water for the operation of the Western Division of the Pennsylvania Mainline Canal between Johnstown and Pittsburgh. Though the dam had been built according to accepted engineering practices, the canal system was obsolete by the time the dam was completed in 1853.

In 1889, Johnstown was home to 30,000 people, many of whom worked in the steel industry. On May 31, the residents were unaware of the danger that steady rain over the course of the previous day had caused. A spillway at the dam became clogged with debris that could not be dislodged.

An engineer at the dam saw warning signs of an impending disaster and rode a horse to the village of South Fork to warn the residents. However, the telegraph lines were down and the warning did not reach Johnstown.

At approximately 3:00 p.m. on May 31, 1889, the South Fork Dam gave way. In less than forty-five minutes, twenty million tons of water poured into the valley below.

Roaring down the narrow path of the Little Conemaugh River, a seventy-foot (21m) wall of water, filled with huge chunks of dam, boulders, and whole trees, smashed into the small town of Mineral

Point and swept away all traces of its existence.

A view from the top of the broken dam.

Next in line was Woodvale, a town of about 1,000, that the torrent smashed with equal ferocity. Scouring its way towards Johnstown, the flood picked up several hundred boxcars, a dozen locomotives, more than 100 houses and a growing number of corpses.

The residents of Johnstown heard the speeding wall of death, a roar like thunder. Next, they saw the dark cloud and mist and spray that preceded it, and were assaulted by a wind that blew down small buildings. Next came the great wall of water sixty-three feet (19m) high that smashed into the city, “crushing houses like eggshells” and snapping trees like toothpicks.

It was all over in ten minutes. But there was more yet to come. The flood met its first serious resistance at the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Stone Bridge, which saved the lives of thousands by not breaking.

After dark, however, the thirty acres of debris, at places forty feet high, that had piled up behind the bridge caught on fire and burned through the night, blanketing the ravaged town in a dark cloud of acrid smoke.

The total death toll was calculated originally as 2,209 people, making the disaster the largest loss of civilian life in the United States at the time.

According to records compiled by The Johnstown Area Heritage Association, bodies were found as far away as Cincinnati, and as late as 1911; 99 entire families died in the flood, including 396 children; 124 women and 198 men were widowed; 98 children were orphaned; and one-third of the dead, 777 people, were never identified; their remains were buried in the “Plot of the Unknown” in Grandview Cemetery in Westmont.

The Conemaugh Valley.

It was the worst flood to hit the U.S. in the 19th century. 1600 homes were destroyed, $17 million in property damage levied (approx. $497 million in 2016), and 4 square miles (10 km2) of downtown Johnstown were completely destroyed.

Debris at the stone bridge covered 30 acres, and clean-up operations were to continue for years. Cambria Iron and Steel’s facilities were heavily damaged; they returned to full production within 18 months.

A lawsuit was filed against the wealthy owners of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club for failing to properly maintain the South Fork Dam, but failed because negligence could not be proven on the part of any individual — a disappointing ruling that would result in changes to liability laws in many states.

Soldiers look over Johnstown from Kernville Hill.

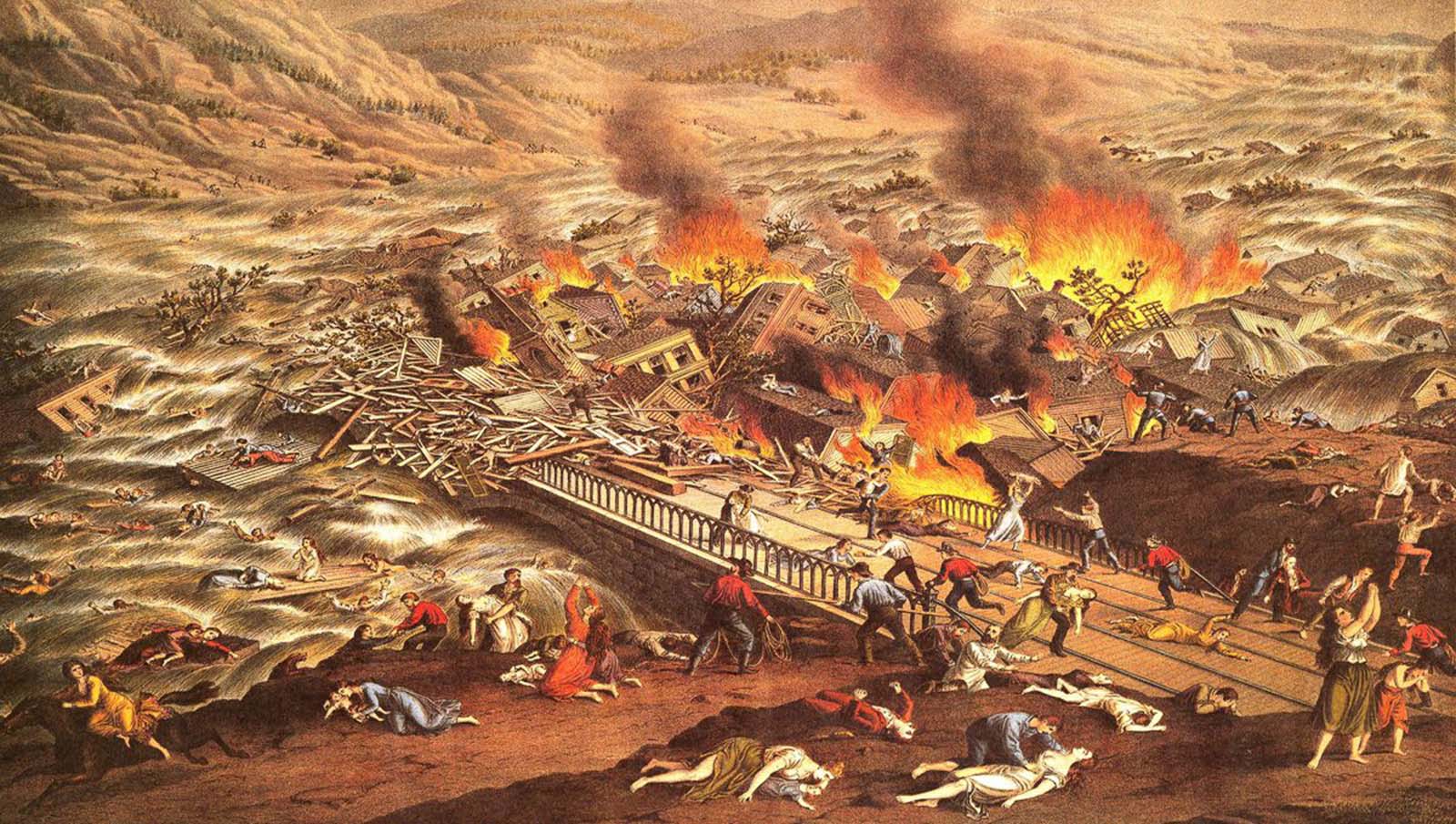

A rendering of the scene at the Stone Bridge.

The ruins of Johnstown.

The dam broke after several days of extremely heavy rainfall, releasing 14.55 million cubic meters of water.

The biblical destruction.

With a volumetric flow rate that temporarily equaled the average flow rate of the Mississippi River, the flood killed more than 2,200 people.

A freight car lies near the damaged Cambria Iron Works warehouse.

Lower Johnstown three days after the flood.

Johnstown’s Main Street is choked with debris.

The American Red Cross, led by Clara Barton and with 50 volunteers, undertook a major disaster relief effort.

Support for victims came from all over the United States and 18 foreign countries.

After the flood, survivors suffered a series of legal defeats in their attempts to recover damages from the dam’s owners.

Relief efforts at the Masonic headquarters.

The ruins of the Sisters of Charity building.

The Cambria Iron Works building.

The camp of the relief corps.

The debris pile at the Stone Bridge.

Volunteers search for bodies in the debris piled up against the stone bridge.

Public indignation at that failure prompted the development in American law changing a fault-based regime to one of strict liability.

The village of Johnstown was founded in 1800 by the Swiss immigrant Joseph Johns (anglicized from “Schantz”) where the Stonycreek and Little Conemaugh rivers joined to form the Conemaugh River.

Working seven days and nights, workmen built a wooden trestle bridge to temporarily replace the huge stone railroad viaduct, which had been destroyed by the flood.

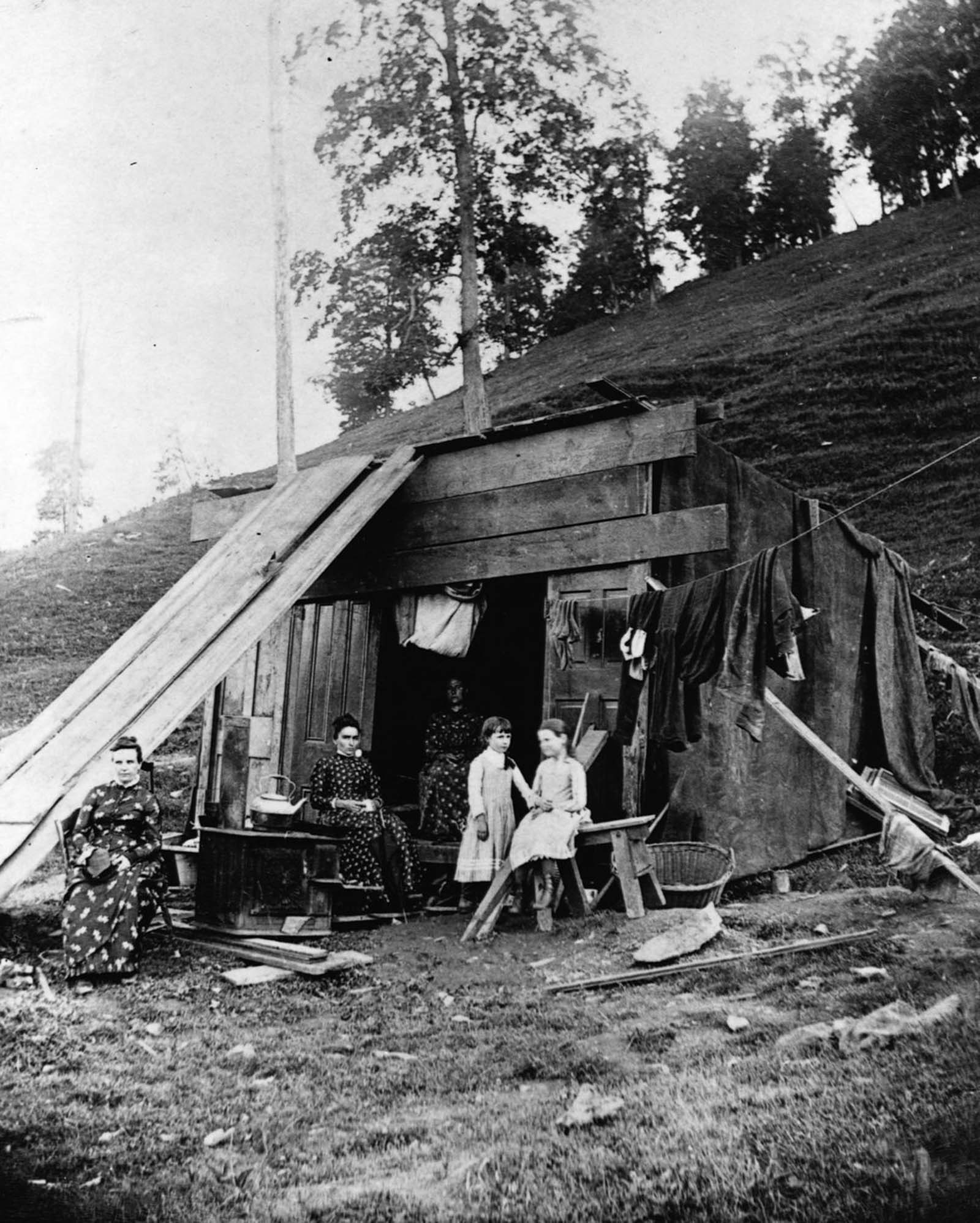

A family of survivors lives in a makeshift shelter in a cave.

A tree protrudes from a house tossed by the flood.

A souvenir stands sells flood memorabilia.

The Johnstown Flood in rare pictures, 1889