In American history, the term “whipping” brings to mind a harsh and haunting punishment from the past. It was a brutal practice that left physical and emotional scars on countless people.

Whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o’ nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc.

Whipping was a common form of punishment during the early colonial period in America. English colonists brought with them a legal tradition that included whipping as a means of disciplining offenders.

It was used for various offenses, including theft, public drunkenness, and disobedience. The severity of the punishment varied depending on the nature of the crime and local laws.

Perhaps one of the most disturbing aspects of whipping in American history was its widespread use as a means of controlling enslaved people.

Enslaved individuals could be subjected to brutal whippings for the slightest perceived infractions or acts of resistance.

Whippings were not only a means of physical punishment but also a tool of psychological terror, used to subjugate and maintain control over enslaved populations.

The 19th century saw significant reforms in the criminal justice system, including a shift away from corporal punishment.

Influential figures like Dorothea Dix advocated for the improvement of prisons and the humane treatment of inmates.

Gradually, whipping as a public spectacle declined, but it continued to be used in some jurisdictions, particularly in the South, well into the 20th century.

By the turn of the nineteenth century, Maryland was the only state that retained a flogging law.

But within a year it was joined by Delaware, and in 1905, Oregon, which enacted a similar provision to Maryland, only to repeal it six years later after considerable public uproar.

Baltimore’s Whipping Post

In the early 20th century, Baltimore was one of the few major American cities where whipping continued to be used as a form of judicial punishment.

This practice was mainly applied in cases of assault and battery or other violent offenses.

Whipping was usually carried out in the Baltimore City Jail, where a designated official administered the punishment using a leather strap or whip.

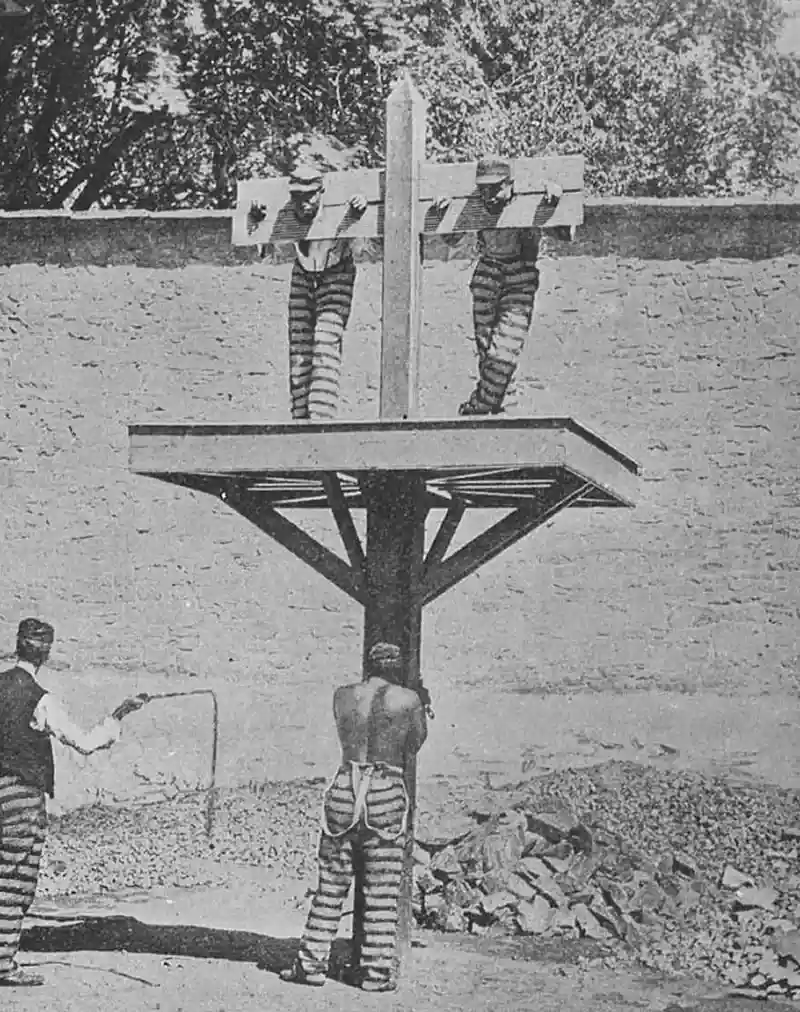

The whipping post pictured above was put into use around 1885 at the Baltimore City Jail, where until 1938, many of those convicted of wife-beating were punished.

The picture above shows a convicted wife-beating punished by whipping. According to the Maryland Center for History and Culture: “On a cold March day, three blue-clad guards strapped Baltimore printer Clyde Miller to a cross-shaped wooden post in the Baltimore City Jail, arms outstretched and naked to the waist.

As 50 witnesses looked on, Miller was brutally flogged 20 times with a cat o’ nine tails—a whip with multiple knotted thongs—at a rate of a lash per second.

After the final blow, Miller, sobbing, whimpering and “half fainting from the pain,” was taken to the prison infirmary.

Sheriff Joe Deegan, the man tasked with carrying out the sentence, remarked afterwards that although he hadn’t relished the task, he was “only the instrument of the law…[and] as long as that law is on the book, I have to abide by it.”

Incredibly, this didn’t occur in 18th or 19th century Maryland—it took place in Baltimore in 1938.

When Clyde Miller was manacled to the smooth, dark surface of the wooden post, he became the last person flogged on Baltimore’s archaic mechanism of punishment, under an obscure 56-year-old law that prescribed flogging for one crime only–wife-beating.

An apparatus similar to this – with pillory on top and whipping post below – used from the colonial period until the early 1800s, resided in Baltimore’s first courthouse on Calvert Street between Lexington and Fayette Street, where today the Battle Monument stands. New County Castle, Delaware, whipping post and pillory, not dated—not part of MdHS’s collection.

The use of whipping in Baltimore drew significant public attention and debate.

Critics argued that it was a cruel and outdated form of punishment that violated the evolving standards of human rights and the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

Supporters of whipping, on the other hand, believed it served as a deterrent to crime.

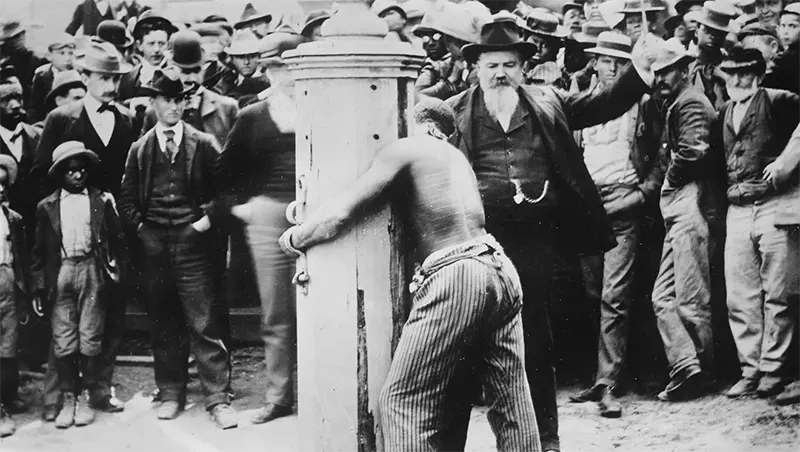

An apparent demonstration in May of 1963 of the by then banned whipping law. (lash marks are evident on the back of the “criminal”) The post was brought up from storage where it had sat for the previous 25 years at the Baltimore City Jail. Within months of this photograph being taken, the whipping post was donated to the Maryland Historical Society, where it remains today.

Ultimately, the practice of whipping in Baltimore came under scrutiny and faced legal challenges.

The criticism and legal pressure eventually led to the abolition of whipping as a judicial punishment in the city in the mid-1950s.

Whipping in Delaware

An undated photograph of the whipping post in Georgetown, Delaware. The post was placed for public view, outside of the Old Sussex County Courthouse, in 1993. The News Journal reports that it was marketed as a tourist attraction.

Delaware, like Maryland, retained whipping as a punishment option well into the 20th century, particularly within its prison system.

The number of lashes administered would vary depending on the severity of the offense and the discretion of prison authorities.

An undated photograph of the whipping post in Georgetown, Delaware. It’s unknown when this whipping post was built, according to the Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs.

One historian estimates that over 1,600 men may have been flogged in the state between 1900 and 1940.

Sixteen men were subjected to the punishment on a single day in May of 1904 on Delaware’s whipping post, nicknamed “Red Hanna.”

These high numbers were probably due to the fact that Delaware had not one, but 24 offenses to which a guilty party could be punished by flogging.

These included such crimes as: embezzlement by a cashier, servant or clerk; perjury or subornation of perjury; willfully and feloniously showing false lights to cause a vessel to be wrecked; burglary with explosives, in a building in which there is a human being, in the nighttime.

An undated photograph of the whipping post in Georgetown, Delaware. From 1900 to 1945, 1,600 people were whipped at posts in Delaware.

Also for burglary with explosives, in a building in which there is no human being, in the nighttime; and finally, bringing a stolen horse, ass, or mule into the state and selling or attempting to sell it.

Over time, as prison reforms took hold and the rehabilitation of inmates became a more central goal, the practice of whipping as a disciplinary measure began to decline.

Ultimately, the law remained in force in Delaware until 1972, with the last flogging occurring in 1952.

Other Old Photos of Whipping Punishment

Photo of a public whipping, a fate that befell one one con man whose game was bilking boarding houses, hotels and summer resorts.

Undated picture.

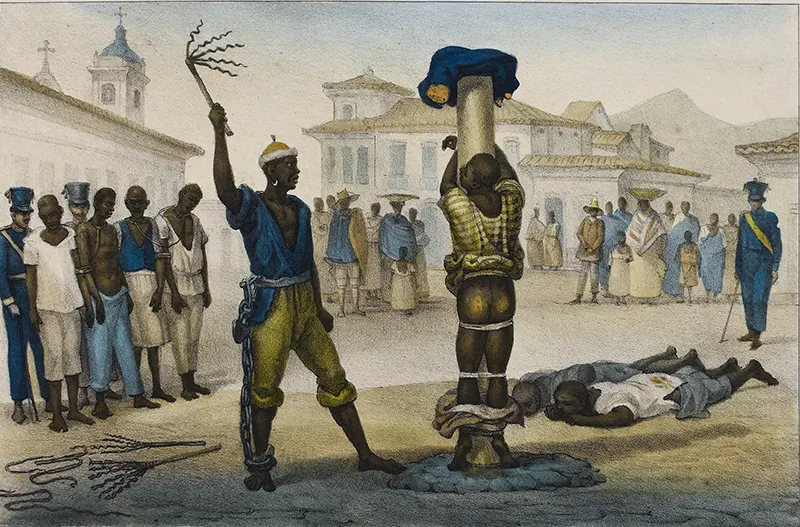

Execution of the flogging punishment. Painting from 1830.

An African-American slave named Gordon, photo taken at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1863. The scars are clearly visible because of keloid formation. (More information about this photo).

Whipping in Military

During the American Revolutionary War, the American Congress raised the legal limit on lashes from 39 to 100 for soldiers who were convicted by courts-martial. Generally, officers were not flogged.

As critics of flogging aboard the ships and vessels of the United States Navy became more vocal, the Department of the Navy began in 1846 to require annual reports of discipline including flogging, and limited the maximum number of lashes to 12.

In total for the years 1846–1847, flogging had been administered a reported 5,036 times on sixty naval vessels. At the urging of New Hampshire Senator John P. Hale, the United States Congress banned flogging on all U.S. ships in September 1850, as part of a then-controversial amendment to a naval appropriations bill.

Hale was inspired by Herman Melville’s “vivid description of flogging, a brutal staple of 19th-century naval discipline” in Melville’s “novelized memoir” White Jacket.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Maryland Center for History and Culture).